iphone video . . . a site for video made PURELY on the iphone, using iMovie, ReelDirector, CinemaFXV, SlowMo, stopmotion or whatever you got!

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Thursday, December 16, 2010

Sunday, December 5, 2010

Got Craft? Fair in Vancouver dec 5 2010

nice, handmade, check the website and you can see all the vendors and their individual sites

http://gotcraft.com/

Friday, December 3, 2010

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Sunday, September 19, 2010

Wednesday, September 8, 2010

Monday, September 6, 2010

Taiwan festival 2010

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Monday, August 30, 2010

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Computer Animation, Made by Hand

A scene from “My Dog Tulip,” coming to Film Forum on Sept. 1. The film is based on a 1956 memoir by J. R. Ackerley (1896-1967), the writer and BBC radio host.

NO one’s four-legged friends were harmed during the making of “My Dog Tulip,” but the roar of Paul and Sandra Fierlinger’s untethered Jack Russell suggests that two-legged strangers might not fare so well.

“Oh, Oscar, stop,” Sandra Fierlinger said, opening the door to the couple’s tree-shrouded cottage on the Main Line, outside Philadelphia. “He’ll be fine, as soon as you get to the other side of the room.”

He wasn’t, it turned out. But even the menacing Oscar couldn’t distract from the room itself: a bank of computer monitors stretched across half the width of the house; beneath them a phalanx of custom-made computers and hard drives crowded one another along the floor. Here the couple put into motion J. R. Ackerley’s 1956 memoir about his late-life “romance” with a German shepherd, taking computer animation into an orbit both new and retrograde: computerized yet hand drawn.

Which didn’t quite make sense until Mr. Fierlinger sat down at what he calls his light table: as his digital “pen” moved across the horizontal surface, a line drawing appeared on the vertical screen, creating the “motion” of two existing images that, when run at 24 frames per second, will be cinema. About 60,000 drawings went into “Tulip.” But no paper. Or plastic.

Opening on Sept. 1 at Film Forum in the South Village, “My Dog Tulip” features the voices of Christopher Plummer as Ackerley, the writer and longtime BBC radio host; Lynn Redgrave, who died in May, as his nettlesome sister; and Isabella Rossellini as a kindly veterinarian. As it happens, nearly everyone involved is a dog lover: the Fierlingers have Gracie, a mix of shepherd and corgi, and Oscar (whose electronically adjusted voice was used when an aggressive bark was called for). Mr. Plummer said in a telephone interview that he grew up around dogs and “prefers them to a lot of humans,” while Ms. Rossellini said that, of course, she is “a huge dog person.”

“I even raise dogs for the blind,” she said via e-mail, adding: “The drawings for the animation are very charming, don’t you think so? I love their work.”

That work has won the Fierlingers a Peabody Award (“Still Life With Animated Dogs,” 2001), and Mr. Fierlinger earned an Oscar nomination for best animated short in 1980 for “It’s So Nice to Have a Wolf Around the House.” Anyone who’s grown up watching “Teeny Little Super Guy” segments on “Sesame Street” has been watching a Fierlinger creation.

Ms. Fierlinger, 55, who has a fine-arts background, adapted her skills to colorizing her husband’s sketches. “I paint with layers, just as I would with traditional animation,” she said. “I make my own brushes and mix my own colors, just as if it were a paper background. But I do it all on the computer.”

Unlike studio cartoons, which often involve computer-generated imagery, the Fierlingers’ work is hands-on, sort of. What’s eliminated is wasted motion: the shuffling of paper, the sharpening of pencils, the setting up of shots. That it still took them three years to make “My Dog Tulip” almost seems surprising. It certainly gave Mr. Plummer pause.

“He said, ‘I was told it’s going to take you three years to do this,’ ” Mr. Fierlinger, 74, recalled, “and I said, ‘Yes, at least.’ He said, ‘I’m going to be dead by then, I’ll never get to see it.’ I told him: ‘I’m roughly about your age, so if you think you’re going to be dead, then so am I, and it will never get done. You won’t miss anything.’ When we met again last year in Toronto, we agreed the time had gone so fast.”

The heart of “My Dog Tulip” is Mr. Ackerley’s story of his late-middle-age relationship with an Alsatian named Tulip. Bittersweet, heartfelt and rendered in an eccentric, expressive style, the movie seems poised to draw dog-loving moviegoers like beagles to bacon. (New Yorker Films, the distributor, is doing grass-roots promotion to dog walkers, vets, pet food stores and bookstores; New York Review of Books Classics is reissuing the Ackerley book.)

But Mr. Fierlinger’s story could be a movie too — and was, actually, in his animated autobiographical 1995 film “Drawn From Memory.” The child of Czech diplomats, he was born in Japan, relocated to the United States as a youngster and then shipped to Czechoslovakia, where his uncle, Zdenek Fierlinger, became the country’s first postwar prime minister, while his father worked in the top echelons of the Soviet puppet government. A boarding-school classmate of Vaclev Havel’s and a member (at least geneaologically) of the ruling elite, Mr. Fierlinger fled to America shortly after his father’s death in 1967.

The Fierlingers use French software called TVPaint; the director Nina Paley, whose “Sita Sings the Blues” was a breakthrough in personalized computer animation, uses the more popular Flash.

“There are many ways to use Flash,” she said, “the most common being with ‘motion tweens’: creating a virtual puppet, and having Flash automatically move the pieces from place to place. That’s commonly called ‘cutout style.’ But you can also use Flash to draw every single frame from scratch if you want. I used a combination in ‘Sita’: mostly cutout style, but also some straight-ahead-style hand-drawing straight into the program.” She also “did some paintings on paper, which I scanned in.”

Not so at Chez Fierlinger, where the forward-thinking animators are cutting themselves loose not just from graphite and cameras but also from traditional avenues of financing and distribution: a children’s film they wanted to make — and are in fact making — centers on Joshua Slocum, the first man to sail around the world solo. It was turned down for financing by the public-television production arm ITVS.

“We thought we could do whatever we wanted,” said Mr. Fierlinger, who is returning to his teaching job at the University of Pennsylvania this term. “Everything we’ve done for PBS has been a success. But they said, ‘We can’t see why children would want to watch this for an hour.’ ”

So they’re doing it in installments, like a graphic novel, and selling it online. “We realize we could do this all on the Internet, for the iPad or similar devices,” Mr. Fierlinger said. “We don’t need a distributor. We don’t even need actors. And the technology is developing so fast that by the time we’re done, there are things we’ll be using that people aren’t even talking about now.”

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

iPhone app: Splice

Description

The power of Hollywood is now with you, anytime, anywhere on your iPhone.

Available on the iPhone 4 and 3GS running iOS4!!!

Splice is the most advanced, portable video editing and audio production mobile applicaton on the market. Splice allows you to create and produce videos from start to finish via your iPhone with no laptop or desktop computer necessary. Hollywood never had it this easy.

Splice puts you in total control, allowing users to assemble video clips, music, photos, visual effects, text, audio mixing, and creative expression, along with exacting synchronization of sound effects and voice-overs. Your only limit is your imagination.

Splice offers a host of special features that cannot be found on any other portable video editing/production app, thereby delivering a high level of sophistication coupled with ease of use.

Splice EXCLUSIVE features include:

• Control and mix for multiple tracks of audio

• Intuitive and easy to use scrub & time line

• Precise synchronization of sound effects and a narration track

• Available on the iPhone 4 and 3GS running iOS4

Other Splice features:

• Simple, easy-to-use ‘drop-and-drag’ features for assembling video clips and photos

• Ability to add music from iTunes or other music sources

• Preloaded with music and sound effects

• Ability to add sound effects, visual effects, transitions and text

Never miss another opportunity to capture those once-in-a-lifetime moments. Your baby‘s first step. Your vacation, party, graduation, family reunion – virtually any event in your life. Or use your creativity to tell a story of your making. If you can think it, you can create it.

Splice levels the playing field, making users the Director, Producer, Writer, Distributor, and even the Star. Total freedom of expression via video has never been easier.

Our award-winning technical team is committed to delivering the best video production application possible. We are excited by the possibilities and value your feedback as we help Splice users share their world with the rest of the world.

Monday, August 16, 2010

iPhone app: PhotoSpeak

More info, well, that's best found in seeing it in action, so check the vids.

Sunday, August 15, 2010

Saturday, August 14, 2010

Video Panorama

It is buggy, but you may not notice as it does get great results, so check it out.

After the official slick hype is an actual panorama I made from a video that is also 100% mine, what do you think?

*****NOTE, it is buggy, it makes very small photos, such as the one I have posted here is only 254kb, it seems to invert all the images, so you will have to edit afterwards, sometimes it just plain doesn't work and you end up with a mess.

Another wonky thing is trying to make a vertical image(done by holding the iPhone in portrait when creating) just goes wrong sometimes, so needs work, but still impressive.

New update v1.8! (Now support iPhone 4 and iPhone 3G S) The EASIEST Panorama Tool ever! No multiple shots! You only need to take a short video!

▶GOOD REVIEWS FROM USERS◀

=============================

This is amazing! I can not believe it can make panorama images in such easy way and the result is overwhelming! It’s a must-have App for who owns an iPhone 3G S!

★★★★★ - From one Twitter user

If you like panorama images, you must not miss this awesome app. Just take a short video and the app takes care of the rest. Really cool!

★★★★★ - From PC Magazine end user

=============================

Video Panorama lets you quickly and easily compose amazing panorama images from video with 2 taps within one minute. With this cool app, your will not be pity when you see beautiful views but without bringing professional camera. It will definitely make more fun for you.

▶USAGE◀

Take a video clip or select a video clip from album

Tip A: if you want to make landscape image, please rotate your iPhone to make the home button on the right, take the video slowly and smoothly (start) from left to right (stop)

Tip B: if you want to make vertical image, please make the home button on the bottom, take the video slowly and smoothly (start) from top to bottom (stop)

The app will help to generate panorama images automatically

Save it to album or send by email

▶FEATURES◀

Stitch Landscape panorama images

Stitch Vertical panorama images

Save to album

Email

▶NOTES◀

iPhone OS 3.1 and iPhone 3G S required.

ORIGINAL BY ME:

Video sex chat service by using the iPhone 4 FaceTime is now available

Now, you have one more way to use iPhone 4 FaceTime: Video sex chat service. iP4Play.com has employed several hot talents, and lets customers to choose to spend time with them interactively. iPhone 4 FaceTime requires wireless connection (unless you jailbreak), so this service will also need Wi-Fi connections.

To use the service, register a free account with your phone number, and choose how long you want to spend. It allows you to choose from 5-20 minutes. The talent will contact you shortly and you will be able to have fun. I hope you won’t be too excited and drop the phone accidentally.

[via Cult of Mac]

Friday, August 13, 2010

iPhone 3G S Hardware Can Record 720p Video, so Why Doesn't It?

Here's a question: If you're building a video-capable successor to the wildly successful iPhone 3G and you choose new hardware that supports 720p-resolution video recording, then why do you cripple it to just VGA resolution?

It's an interesting question because that's exactly what Apple has done. The discovery was made by Rapid Repair, which got hold of a newly-on sale iPhone 3G S at midnight in Paris, and wasted no time tearing it apart to find out what its internals were like. The answer is that they're extremely similar to the iPhone 3G, which may be no surprise when you think that the 3G S is an evolutionary step up from the 3G, and even has identical screen tech and housing for the phone.

Except for the new camera and-updated processor, of course. Which is where the interesting 720p capability comes in. The camera shoots 3-megapixel stills, and thus could be commanded to shoot 720p video--it's got more than enough pixels to spare, and the speedier 600MHz processor in the phone should be easily capable of the increased bandwidth required by 720p video. Why has Apple chosen to limit it to VGA resolution? It seems a slightly odd move, given that there are smartphones out there that shoot still imagery at 12-megapixels and can do full HD video.

The answer is a mystery, but we can guess one probable cause. It's the same reason why the 3G S's new processor, which is capable of 833MHz speeds, is choked down to just 600MHz: Battery life. Apple's aware that the iPhone's battery is a bit small, and protects the battery performance as much as possible--its quoted as the chief reason there's no background app capability on the phone. 720p video recording and a faster processor would just eat into the battery a whole lot more.

And the reason the battery is limited is that Apple chose to stick with the same iPhone casing. If Apple would've adjusted the physical design of the phone, Apple could've easily included a bigger capacity battery. This seems to be one of those strange moments when an aesthetic design decision has squashed the opportunity to sell the iPhone with a killer feature: HD video recording.

[Rapid Repair via Engadget]

Monday, August 9, 2010

Sunday, August 8, 2010

First look at Display Recorder: high quality recorder to show what you did on the iPhone

iPhone is so easy to use, but there are still some friends who can’t figure out how to do some specific tasks. Taking screenshots cannot easily tell the story, making video is the best choice. Display Recorder(US$4.99) from Cydia can record the iPhone and iPad screen without any difficult setup.

Before actually start using it, go into settings and choose “Display Recorder”. It allows to choose the highest framerate to 25. But, I would suggest to keep it as 20. The video can be recorded in portrait mode or landscape mode. In the bottom part, you can set the YouTube login in order to upload the video instantly in the future.

The activation method of Display Recorder would be short press the power button. This can be changed in the settings. After it has started the recording, just do what you want to do on the screen. Short press the power button again will end the recording.

I have tested the Display Recorder on the iPhone 4. It will make the phone restart if I chose to do some heavy tasks like playing videos. In general, it works perfectly. The best part is that it can show taps with little white circle in the video. To my surprise, the video quality is awesome and clear.

[via winandmac]

Saturday, August 7, 2010

Flash / Frash Ported to iPhone 4 !! [Video]

The title says it all! Yes, you can now get very alpha version of Flash (aka Frash) running right on your iPhone 4. Previously, we showed you how to install Flash (Frash) on iPad. And now folks at Grant Pannell site has managed to compile an iPhone 4 version of Flash. The credit for this of course goes to Comex, the guy behind Spirit and JailbreakMe tools for iOS devices. Without his hard work, this surely wouldn’t have been possible.

Simply follow the instructions posted below to get it working on your iPhone 4. According to the source, this version of Flash (Frash) will also work on iPhone 3GS, iPad (on 3.2.1) and iPod touches. I have tested it on iPhone 4, running iOS 4.0.1 only and can confirm that it works. You can see it in the video embedded below.

Simply follow the instructions posted below to get it working on your iPhone 4. According to the source, this version of Flash (Frash) will also work on iPhone 3GS, iPad (on 3.2.1) and iPod touches. I have tested it on iPhone 4, running iOS 4.0.1 only and can confirm that it works. You can see it in the video embedded below.

The installation instructions..

Warning Note: This guide is for testing & educational purposes only. Follow it on your own risk. I’m not responsible for any loss of important data or malfunctioning of your iPhone.

Step 1: First up, you will need to jailbreak your iOS device. Follow the guide posted here to jailbreak your iPhone 4 with JailbreakMe, here to jailbreak your iPod touch 3G and 2G, and here to jailbreak your iPad.

Step 2: Next, you will need to install OpenSSH. To do this, Open Cydia, touch on “Search” tab and then search for “OpenSSH”. Install this app and reboot your iPhone.

Step 2: Next, you will need to install OpenSSH. To do this, Open Cydia, touch on “Search” tab and then search for “OpenSSH”. Install this app and reboot your iPhone.

Step 3: Connect your iPhone with your computer. Make sure iTunes is not running.

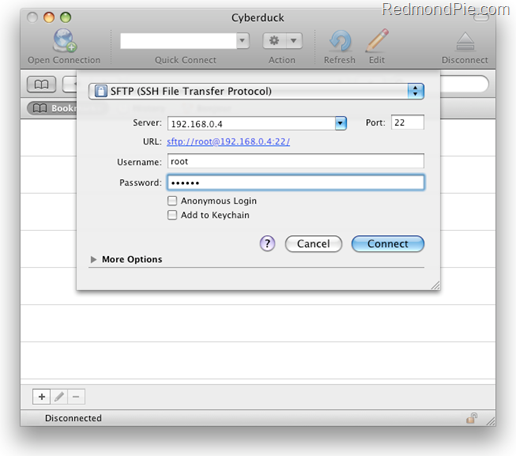

Step 4: Download and install Cyberduck for Mac or WinSCP for Windows. Enter the following details to login to your iPhone:

- Server: The IP address of your iPhone/iPad/iPod touch. Settings –> WiFi –> <Your Network Name>

- Username: root

- Password: alpine

- Protocol: SFTP (SSH File Transfer Protocol)

- Hostname: The IP address of your iPhone/iPad/iPod touch. Setting –> WiFi –> <Your Network Name>

- User name: root

- Password: alpine

- Protocol: SCP

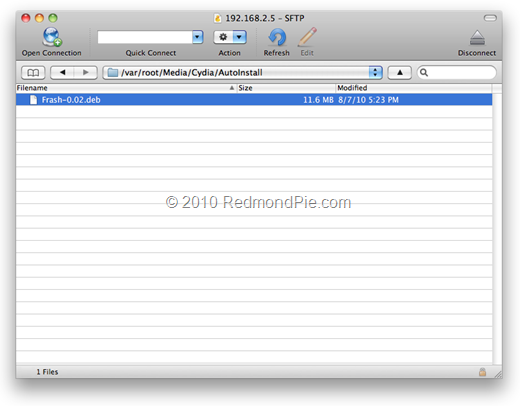

Step 5: Download Frash-0.02.deb file from the source link given below.

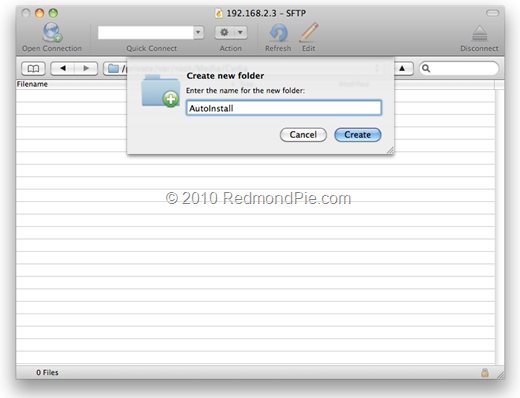

Step 6: Navigate to /var/root/Media directory and create a folder named “Cydia”. Inside this Cydia folder, create another folder and name it “AutoInstall”.

Step 7: Copy over the Frash-0.02.deb file in this “AutoInstall” folder.

Step 8: Restart your iPhone and you are done. Now simply browse any Flash based site, click on the “Flash” text to play the Flash content.

Last but not the least, Credits: Comex for the Frash port, Grant Pannell for iPhone 4 compilation. [Thanks to Youtnell for sending this in!]

[via Redmondpie]

Friday, August 6, 2010

Five freaking awesome FaceTime hacks -- and a few handy tips

We've all been using FaceTime like crazy here at TUAW central -- it's really great to be able to conference with friends in real time without having to arrange things in advance. Nearly all of us have been video-conferencing-ready for years. But with the iPhone 4, there's no more "Do you have iChat set up?" (or Skype) or "Can I call you now?" time-wasting prologues.

We've all been using FaceTime like crazy here at TUAW central -- it's really great to be able to conference with friends in real time without having to arrange things in advance. Nearly all of us have been video-conferencing-ready for years. But with the iPhone 4, there's no more "Do you have iChat set up?" (or Skype) or "Can I call you now?" time-wasting prologues. Instead, we can just call. Knowing that your friends have iPhone 4's makes video conferencing incredibly easy. You don't have to call or text to arrange the call, you just place it and you're immediately good to go. We may have already had webcam equipment on hand but it's only with the iPhone 4 that, at least here at TUAW, that we're actually using video calling.

With that in mind, we've been seeing how far we can push the technology. We've put together a list of the coolest techniques that we've actually tried out and tested and can confirm as working. Without any special ordering, here they are.

Call Internationally for free! [No special hacking required] Got a business colleague in Switzerland that you need to talk to for a current project? Do you have family overseas or otherwise outside your normal calling plan? If they've enabled FaceTime in Settings and activated their service, you can chat over international boundries or across the ocean for free.

Once you've entered contact details, FaceTime availability automatically shows up in Contacts. Don't forget to add the "+" sign needed for International calling. Connect to a Wi-Fi network, tap the FaceTime button, and you're good to go.

TUAW tested US to Europe calling and found the response time and video quality to be excellent. There were no significant lags beyond what you'd normally expect with VoIP, i.e. somewhere between hardly noticeable and nonexistent.

Call home from a plane! [No special hacking required] If your airplane offers in-air Wi-Fi that allows FaceTime traffic, you can call home while cruising thousands of feet above the ground. When calling from a plane, you'll want to use a headset with a microphone as social conditions and ambient noise can make it awkward to talk at normal volumes when surrounded by neighbors trying to catch up on their reading or watch movies. But if the passengers are accommodating and your in-flight service allows the FaceTime bandwidth, it's a really exciting way to keep in touch while on the go.

Project your FaceTime chat on TV! [Requires jailbreak] Imagine you're using FaceTime at a large planning meeting. Rather than put your client on speaker phone, why not channel the FaceTime audio and video out to TV, instead? We used Ryan Petrich's $1.99 DisplayOut software to mirror FaceTime through both a composite video-out cable and via an Apple VGA connector.

The long cables we tested with allowed us to pass the iPhone 4 from person to person, allowing each one to speak directly to the remote party while allowing all participants to view the conversation on the central TV. If we had wanted to, we could have passed the signal through a recorder (DVD recorder or DVR) to archive the meeting as well.

We also tested TVOut2, a free alternative. TVOut2 provides a less customizable presentation and needed a bit of fussing to get it to work properly with the iPhone 4. Once (finally) set up and kickstarted by using some third party video out apps, TVOut2 properly mirrored FaceTime with a good frame rate but a relatively small onscreen display. It should be noted that the display size can be customized rather laboriously in the TVOut2 settings panel.

Just in its initial iPhone 4 release today, TVOut2 should be improving over the next few weeks. It holds the promise of a nice, free utility. However, for just two bucks more, DisplayOut offers a lot more features and reliability in its current release and remains our TUAW recommended solution.

Record your FaceTime chat! [Requires jailbreak] Although Ryan Petrich's $4.99 DisplayRecorder does not record audio (yet!) it simplifies all screen recording tasks, including recording your FaceTime chat without needing video out cables. When installed, just press and hold the Sleep/Wake button for two seconds. A dialog appears allowing you to start recording. When you're ready to finish, press and hold another two seconds.

Once recorded, you can upload your videos directly to YouTube or serve them over your local WiFi network using a Web Server interface. The video we recorded during our TUAW tests had acceptable resolution and frame rates. A two and a half minute no-audio call ended up occupying slightly over 165 MB of video. We missed having audio (hopefully that will be added soon) but being able to archive the video itself was a lovely treat.

Place FaceTime calls over 3G! [Some solutions require jailbreak] Although we cannot recommend using FaceTime over 3G on a regular basis (it uses about 3 MB per minute), there are times we understand when you're not near Wi-Fi and have compelling reasons to need video dialog. We tested out four separate solutions for 3G FaceTime connections and rated them from least reliable to most reliable.

At the bottom of the pack was MiFi. This 3G powered Wi-Fi hotspot solution from Sprint kept cutting out during our tests, allowing us to talk only a minute or two at a time, with repeated freezes and call drops. (We're told that Clear's similar 3G/4G iSpot solution is currently a no-go with iPhone 4.)

Next, in terms of performance, was MyWi. MyWi creates a WiFi hotspot using a jailbroken iPhone's 3G service. We tested using a 3GS for the hotspot and connecting to that hotspot with an iPhone 4. MyWi performed better than the MiFi but had significant service interruptions.

Performing second best in our tests, and providing a huge improvement over the hotspot solutions, was 3G Unrestrictor from Kim Streich. Offering a native on-iPhone solution, it outperformed both MiFi and MyWi but it was slightly less reliable during our tests in terms of audio and video than Intelliborn's My3G, another native application.

3G Unrestrictor's performance must be weighed against a rather significant My3G bug -- when installed, you cannot use your iPhone for native software development. So at this time, we recommend 3G Unrestrictor over My3G. (Update: Intelliborn tells TUAW that the My3G development bug has been resolved. Check Cydia and the Rock store for updates.)

While we cannot recommend 3G FaceTime calls for regular use (think of the children, think of AT&T, think of the data infrastructure, think of the 3MB per minute), having the tools on-hand can prove helpful when the need does arise.

And now for a few handy tips...

Don't forget to enable FaceTime in settings! You must both enable FaceTime and allow it to fully activate before you can join in on FaceTime chatting. Activating your FaceTime service allows the Phone app to call home to Apple and display the FaceTime button when others look at your Contacts page.

Call Widescreen! We were surprised at how many FaceTime users of our acquaintance didn't realize that FaceTime works both in landscape as well as portrait orientation. Feel free to turn your iPhone on its side while chatting and enjoy a more panoramic view. (Even if that panoramic view is of Sande's nostrils.)

Use sign language! [No special hacking required, but a harmonica holder may help] If you need to sign over your phone or otherwise use a hands-free approach, consider putting together a FaceTime hanger solution like the FaceHanger we posted about recently on TUAW. Having an elevated (not just table-level) holder will free up your hands while providing a good angle for FaceTime chatting.

Hold up pictures and documents! The resolution quality for the transferred image is actually quite awesome. I was able to present text to the FaceTime camera that other TUAW team members could easily read from their end, even during our 3G service tests. Just keep your documents still when displaying them.

1-888-FaceTime no longer works! Apple is no longer providing live demos of their FaceTime service. In recent weeks, a call to 1-888-FaceTime leads to a recorded message that instructs you to visit the Apple website for more FaceTime information.

FaceTime isn't always reliable! If you're having troubles with your FaceTime connections, be aware that the FaceTime servers occasionally have their issues. You may simply want to try again later. If you want to learn more about how the FaceTime service works under the hood, here's a great series of articles for you to check out over at Packetstan. Part 1 • Part 2 • Part 3

And don't forget, boys and girls, it's never good to FaceTime while driving! (Thanks, Optimo)

Hate RockApp? 3G Unrestrictor supports FaceTime over 3G also

We told you My3G allows users to use FaceTime over 3G, but it requires to install the RockApp. In Cydia, 3G Unrestrictor has just updated to 2.2-3. No RockApp is required. The new version supports FaceTime also. It costs the same like My3G at US$3.99. Personally, I love 3G Unrestrictor since it’s a lighter app.

Thursday, August 5, 2010

MiTube app flies high but is quickly shot down

You kinda knew it was going to happen. Earlier this week the app store approved MiTube, a YouTube app that allowed you to both view and download videos. Sounded like a great idea, and the app was free, but YouTube is not exactly a downloading service, and the clock had to be ticking on the viability of MiTube.

You kinda knew it was going to happen. Earlier this week the app store approved MiTube, a YouTube app that allowed you to both view and download videos. Sounded like a great idea, and the app was free, but YouTube is not exactly a downloading service, and the clock had to be ticking on the viability of MiTube.

Kerplonk! It's gone. Getting the app yanked is not a big surprise. How it ever got in the app store is a bigger question. Just a couple of weeks ago HandyLight was pulled. It looked like a flashlight app, but in fact it had hidden features that allowed you to tether an iPad or a laptop to your iPhone and share your 3G signal. Apple approved it, then pulled it when the word got out of what the app really did.

Apple has every right to control the app store, but these approvals followed by a quick yank are sort of embarrassing.

By the way, if your iPhone is jailbroken there is always MXTube,

[Via iLounge]

iPhone 4 Video capture and Facetime + MMS frameRate limit removed !

here is the link but it is a member forum so I'll just put the basic info here and encourage you to become a member of the top iPhone forum around.

iPhone 4 Video capture and Facetime + MMS Rate limit remo...

"There is a compression that the iphone does when you send a mms message or when you record from The front facing camera

The FPS is capped to 15 min and 15 max in the plist ..

I was able to get them at 30 with no issues at all ..

Next i tried them on the Facetime settings ... and I Was able to boost the FPS from 15 fps to 30 Fps

placed two Facetime Calls and needless to say as long as your Wifi is strong the calls looked amazing. "

..."all done editting plist.

It seems that right now the MMS takes ALOT longer To Send but the compression is alot better "

...Also allows you to change what filters are used when the Camera is used. and also the FPS cap on Facetime and front facing cam.

careful since I dont know at the moment what might screw something up.

removed Limit from Email Compression as well...

I found a few things about Facebook uploading... has this been enabled as of yet ?

Also found all the settings for the camera front and back.

such as exposer ... Flash Time ... red eye reduction... I think I might try to Put Together a simple app that will let you Adjust all this without having to mess with files... but this will take me a little time. there is alot here guys .. maybe if someone wants to lend A hand ?

starting to seem like a trade off.... clear sound or clear video.... not both due to carrier limit on MMS size...

but the limit to youtube has also been removed .

Facebook now uploads native 720p video with no use for another app like pixelpipe

lots more info...CAREFUL though kind of for experts with jailbroken devices

can screw up your data and wifi if NOT CAREFUL and backup everything and read twice, so not broken twice !

Wednesday, August 4, 2010

Everything You Need To Know And More About iPhone Video

In 2005, Apple introduced their first portable device that could play video - the 5th generation iPod, which came equipped with a 320x240 color screen. Immediately after the release of the device, Apple began offering video content in their iTunes store, which prior to that only sold music. Apple dove deeper into the video realm by releasing Apple TV, and then later creating a device, which on top of being a touch screen cell phone, was the first to have wide screen video. The iPhone, with its 480x320 screen, is a spectacular gadget for watching videos on-the-go. This article will cover absolutely everything there is to know about video on the iPhone - where to get it, formats, converting, video apps, video hacks, video accessories, and more.

Formats

The iPhone plays video in the following formats: MPEG-4 and H.264 codec. Most video available on the internet (like the stuff you download) is most commonly in DivX, WMV, or QuickTime formats. Commercial DVDs are all in MPEG-2 format, while most video cameras are in uncompressed digital video format (DV) or MPEG-2. All the videos on iTunes are in H.264 format exclusively. While H.264 takes longer to encode than MPEG-4, it provides a better quality video (for an equally sized file).

Why MPEG-4/H.264 Codecs?

Some people may be under the impression that Apple chose these formats just to make life harder, forcing us to use converters and such to get video on the iPhone. Others think that it's a ploy to drive more people to purchasing video from iTunes (since it's the easiest and quickest way). However, that is completely wrong. Apple chose MPEG-4 and H.264 (which is just like an improved version of MPEG-4) for very good reasons:

It's an open and established standard

It has a high quality to size ratio (better quality, less space occupied)

It maximizes battery life (other formats...such as DivX...would drain the battery)

Background Info

As you probably know, most video that you deal with is not in iPod/iPhone format. Downloaded video, TV recordings, DVD recorders, video cameras, and everything else, produces video that needs to be converted in order to be compatible wit the iPhone and iPod Touch.

There are a ton of options out there when it comes to converting video. First of all, you need just a bit of background knowledge and a minor terminology lesson so you can understand what's going on when you're converting video.

Some common terms...

Resolution: The dimensions of the screen image, measured in the number of pixels. The iPhone's resolution is 480x320.

Bit Rate: The amount of data encoded to make one second of video playback, measured in kbps (kilobits per second) or mbps (megabits per second). A higher resolution and bit rate result in what we call "high quality video".

Frame Rate: A measure of how many frames (or distinct images, like photographs) pass per second in a video. This is simple to visualize since a video is nothing more than a collection of photographs passing by in a really fast slide show. Frame rate is measured in FPS (frames per second). All digital video (everything that is broadcast on TV and commonly referred to as NTSC) is in 30 fps, while all the filmed movies (what you see in a movie theater) are in 24fps.

Interestingly enough, the reason that we can now shrink down video file sizes is thanks to some geniuses that figured out that not every single frame needs to be encoded. Rather, there are reference frames, and only differences to the reference frame are "written in code". For example, if you're watching a video of a person running down the beach, not that much is changing in the background. The initial image is taken as the reference frame, and then only the pixel changes of the man's motion appear in code.

Aspect Ratio: The ratio of an images width to its height, such as 4:3 or 16:9. Note that the aspect ratio is closely related to the resolution. A 640x480 video is 4:3, because 640/480 = 1.33, which is the same as 4:3. If a video's aspect ratio doesn't match the resolution, black bars are often added around the video.

All of these terms will be seen in every video converting tool, so it's good to know what they mean. Don't worry, while you can customize these settings, most times the programs will have everything preset for you.

Video Converting Tools:

Handbrake

Handbrake can convert your DVDs to a digital, iPhone friendly MPEG-4 format. It's free, and works with both Mac and Windows. It's the most commonly used application for converting DVDs to MP4.

iSquint

iSquint can convert any file to MPEG-4 format and automatically add the resulting file to your iTunes library. It's free, and is available for Mac OS X only. While the developers discontinued iSquint, it can still be downloaded.

Any Video Converter

Any Video Converter can convert virtually all file formats to MPEG-4. It's free, and is available for Windows only.

Videora

Videora is a set of applications, each tailored for a specific handheld device, that convert video to the appropriate file format. It's free, and for Windows only.

ConvertTube

ConvertTube allows you to download YouTube videos directly to the computer, iPod, iPhone, or PSP. Simply enter the YouTube URL, select your device, and wait.

MPEG Streamclip

MPEG Streamclip is great for converting standard video formats to MP4. It's free and available for Mac only.

For recording TV shows and converting them to various file formats, check out...

EyeTVTiVo Decode Manager

MyTV To Go

Hauppauge Wing

To convert home videos (recorded on your own camcorder), use the basic...

iMovie (Mac)

Windows Movie Maker (Windows)

Other DVD decryptors include...

DVD43

Roxio Crunch

Nero

Where To Get Video:

The easiest place to get videos for your iPhone is, of course, iTunes. Although you'll be paying money, you'll be saving hassle. Since the internet people almost always (read: absolutely always) prefer to get things free, you'll have to be creative. There is a excellent site called OVGuide, the Online Video Guide, which can guide you to great places to download videos. You can also use your favorite torrent site...there's a bunch out there.

iPhone Video Apps:

TV.com

TV.com, a CBS app, offers a whole lot of clips and media. But what anyone really cares about is full episodes of TV shows, and it has lots of them.

Price: Free

SlingPlayer Mobile

SlingPlayer Mobile lets you watch the TV shows and movies on your SlingBox from your iPhone, no matter where you are. In other words, if you own a Slingbox, you can watch anything from your TV on your iPhone or iPod Touch. You can even control the DVR. While the app required WiFi, there's a hack to get it running on 3G.

Price: $29.99

MLB.com At Bat 2009

While the application offers a ton of baseball stuff, one feature makes it worth the $10: You can watch live baseball games on your iPhone or iPod Touch. If you're a baseball fan...enough said.

Price: $9.99

TMZ

The famous celebrity gossip site's iPhone app is pretty much a one stop shop for all the dirt. While they've got photos and stories, the videos are by far the best. It's like watching TMZ without hearing their annoying intros.

Price: Free

How To Videos from Howcast.com

Whenever you're confused about how to go about getting a seemingly simple task done, this app can help. Whether you need some visual cues on how to tie a tie, or you're just curious how to pick a lock, video manuals can be found on Howcast.

Price: Free

iVideo Cocktails: Watch it! Shake it! Drink it!

When you're trying to serve drinks at a party, there's nothing cool about having to go to the computer and print out a recipe, only to stand there looking like you're the complete opposite of suave. With this app, you can choose a drink, watch a quick video, and shake it up. With a huge library of drinks, it's worth 2 bucks.

Price: $1.99

netTV

This app offers WiFi streaming from over 200 live channels coming from all over the world. Sometimes it works great, other times there are connection issues...but we had success with it. A lot of new channels work only on the iPhone 3GS. Unfortunately, WiFi is required.

Price: $2.99

Television

Television allows users to stream pre-recorded video from: CNN, CBS, FOX, AP, NBC, HBO, ESPN, CNBC, Comedy Central, VH1, Onion Network, College Humor TV, Digg.TV, Rocketboom, Make, YouTube, Movie trailers, G4, Slate, CNET, National Geographic, SKY, Reuters, and more. It's a great app.

Price: $2.99

Orb Live

If you have an Orb compatible TV Tuner for your PC, then you can stream any video (or media in general) from your computer to your iPhone or iPod Touch. No syncing necessary, it's all wireless. Find out more about Orb here.

Price: $9.99 (and free lite version)

Although obviously everyone already knows of YouTube, it wouldn't be fair not to mention it. YouTube is by far the best video application for the Apple iPhone. The library of videos is so vast that you could probably watch it for the next 100 years...so while all these extra applications are great, keep YouTube in mind. Nothing can trump it.

Online Streaming:

Akamai

Simply open up your iPhone's mobile Safari browser, and go to iphone.akamai.com. The site streams video live from NASA TV, FoxBusiness, USA Today, NPR, Discovery Channel, MTV, Nickelodeon, NBC, and more. Learn more here.

Hollywood Pocket

Hollywood Pocket is great if you're into classic movies. The app streams full (old) movies right to your iPhone. Learn more here.

iPhone Video Hacks and Apps for Jailbroken iPhones:

To use these applications you will first need to jailbreak your iPhone. Go here for a simple guide to jailbreaking your phone.

MXTube

MX Tube is a simple (and awesome) application that allows users to save YouTube videos to their iPhone's library for offline viewing. The app works flawlessly and is extremely popular in the jailbroken iPhone community.

iTransmogrify

iTransmogrify allows iPhone users to watch embedded Flash video content. Watch it in action:

Hulu

Hulu has a native iPhone app.

Qik

Qik is an entirely different type of application - it allows you to broadcast video to the internet live from your iPhone. You don't even need an iPhone 3GS. It's quite amazing...go here to find out more, including how it works and how to get it.

Accessories:

MyVu

MyVu allow you to watch video from your iPhone or iPod inside their patented MyVu "sunglasses". The prices are all in the ballpark of $300. Find out more here.

Joby's Gorilla Mobile

This accessory allows you to prop up your iPhone on your table, or around any fixture you want. Not exactly necessary, but nevertheless, it's very cool. Find out more here, and get it here.

Factron iPhone Case

This is a bit ridiculous, but for the photographers out there who love their iPhones...this will make your mouth water. The case includes wide angle, closeup, and fisheye lenses that screw onto the back. This thing runs $200. Buy it here (no surprise, it's Japanese).

SEG Clip

This USB Antenna allows iPhoners in Japan to stream television live on their iPhones. Users simply plug the thing into their computers, download a companion app on their phones, and stream away. It's basically like TiVo for your iPhone...all for $68. Of course, it's only available in Japan.

iCooly iPhone Stand

There are tons of iPhone "video stands" out there, that prop your iPhone up on the table in a very feng shui kind of way. While stands like this one may cost you a few bucks, there are also lots of DIY iPhone stands made out of things paper clips, business cards, and even a dollar bill.

_____________________________________________________________________________

The iPhone, although it only has a 3.5 inch screen, is probably the #3 most commonly used device for watching video, following the television and the computer. So while it's not your primary source of video, it's still a very frequently used one...and when you're on the go, it's the only option. With the information provided above, you'll be able to get the most out of your iPhone as a portable video player.

Please recommend some other iPhone video apps, hacks, accessories, or conversion tools that we failed to mention in the comments. Thanks!